Disclaimer: Some links are affiliate links, meaning I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. See my full disclaimer for more info.

Professional Barriers and Mental Health Access: An Analysis of Social Work Licensure Portability and the Benefits of the Interstate Social Work Compact

Ali Myers

Abstract

Presently, the social work licensing structure varies across the United States. Each state has their own regulatory body that sets the rules and regulations governing social work practice. The social work profession has no licensure portability, and providers must get licensed individually in each state. Education requirements, supervision, and examination requirements may change across each state. Additionally, states govern their own scopes of practice and licensure titles. The lack of consistency in social work standards throughout the United States creates significant professional barriers for social workers. Further, the current structure limits access to safe and adequate mental health treatment. This paper discusses the implications of the current licensure framework and potential solutions.

Introduction

Current social work licensing structures pose significant problems for the 500,000 licensed social workers within the United States and U.S. territories. Presently, social workers are required to obtain individual licenses to practice separately in each state the individual will provide services (National Center for Interstate Compacts, 2024). Given this requirement, social workers may have to complete multiple applications, pay multiple fees, and potentially take multiple licensing exams to become legally licensed (Landsman and Rathman, 2023). Obtaining licensure is further complicated by inconsistent licensing titles and inconsistent scopes of practice. Furthermore, individual states have their own governing bodies that set rules and regulations that define social work scope of practice, types of licenses, educational requirements, supervision requirements, continuing education requirements, and experience (Apgar, 2022; Apgar and Nienow, 2023; Cooper-Bolinsky, 2019).

The current licensing structure disproportionately affects rural populations (Landsman and Rathman, 2023), children (Musburger et al., 2023), and military families (Kersey, 2013). Fewer mental health providers are available to serve rural populations and access to adequately trained providers may be limited. In some circumstances, providers from surrounding states must obtain licensure in multiple states to serve small rural communities (Landsman and Rathman, 2023. Access to social workers specializing in child mental health is also limited in some areas (Musburger et al., 2023). Additionally, military families are disproportionately affected because they have to relocate often. The professional opportunities within the family are negatively impacted because the professional social worker will have to obtain a separate license with each move (Kersey, 2013).

Background

In most states, social workers must obtain a degree from an institution of higher education that is accredited by the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE). The CSWE is recognized by the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA) to accredit social work programs (Council on Social Work Education, 2022). Currently the CSWE only accredits baccalaureate and master’s level programs; however, they are working towards accrediting doctorate level programs (CSWE, 2020). The CSWE requires that institutions of higher education prepare students for competent, ethical, and safe practice upon graduation through mastering nine core competencies with advanced practice behaviors (CSWE, 2022).

Upon graduation from a CSWE program, social workers must look to their individual licensing boards for licensing guidance. Each state within the U.S. sets their own requirements for licensure and licensure titles (Apgar, 2022). Most states have multiple levels of licensure and within the licensure process, most social workers will have to sit for a professional exam. Many states utilize a standardized exam created by the Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB) prior to issuing a social work license. ASWB offers social work licensing exams at the associate, bachelors, masters, advanced generalist, and clinical exam levels. While individual states do require examinations for most licensure types, there are some states that allow certain levels of social work licensure to be licensed without examination. For example, West Virginia has five levels of licensure, each requiring a certain level of ASWB exam. California only has two levels of licensure, and the Associate Clinical Social Worker level does not require an examination (ASWB, 2024).

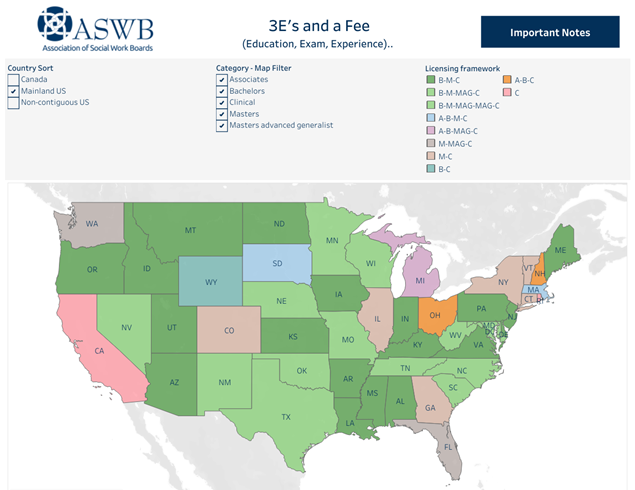

Despite the CSWE setting the educational standards for institutions for students to master within their education. There are not consistent social work licensing titles or scopes of practice across the United States. The ASWB utilizes software to produce charts and maps with educational, examination, and experience requirements by state. The 3E’s and a Fee map shown in Figure 1 displays the licensing framework by state. The licensure framework includes bachelor, master, clinical, masters advanced generalist, associates, and masters advanced generalist clinical. One can see from the map that two states, Ohio, and New Hampshire, have an associate, bachelors, and clinical level of licensure.

California is the only state that exclusively has clinical licensure types. Michigan has an associate level, bachelor, masters advanced generalist, and clinical level licensure. Eighteen states only have bachelor, masters, and clinical levels. Fourteen states, including West Virginia, have bachelor, masters, masters advanced generalist, clinical, and masters advanced generalist clinical levels. These variations in licensure framework make it incredibly challenging to obtain licensure in different states throughout the country. This may also make the scope of social work practice confusing, given the wide variation in practice levels (ASWB, 2024).

Figure 1.1

3 E’s and a Fee

ASWB, 2024

Social Work Licensure Portability

In 2012, Michelle Obama asserted that a change was needed in professional licensing processes. Military families were struggling to obtain professional employment upon relocation due to having to obtain a new license to practice. At that time, one-third of military spouses had a professional license or needed to obtain one. The process to obtain the license was slowed by application processes, fees, and sometimes additional testing requirements upon relocation. At times, the educational and supervision requirements did not align from one area to the next (Kersey, 2013).

Seven years after Michele Obama’s proposal for changes, COVID19 hit the world, highlighting global struggles with safe access to mental health treatment. Telehealth became essential throughout the pandemic, yet individuals still struggled to access providers that were adequately trained. Social work providers were unable to obtain licensure to practice in the areas needed due to the lack of licensure portability (Apgar, 2022). Further, some states did not have legislation enacted for licensed clinical social workers, entirely removing their ability to provide psychotherapeutic services to individuals that needed it (Cooper-Bolinksey, 2019).

In 2023, Landsman and Rathman (2023) published a study highlighting the struggle of rural Iowa communities gaining access to safe and adequate mental health treatment. The authors reported that social workers in six states bordering Iowa were having to get licensed in multiple states to provide services to rural communities within Iowa. This is particularly concerning given the increased risk of suicide in rural areas and potential for dual relationships.

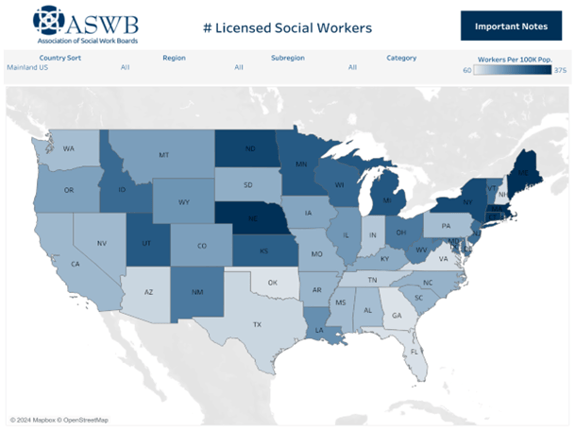

The concerns with the number of social workers for the population is not limited to Iowa. Figure 2, Number of Licensed Social Workers, provided by ASWB (2024) shows the number of social workers ranging from 62 to 375 per 100,000 population. Many rural areas are a lighter blue indicating fewer social workers.

Figure 2

Number of Licensed Social Workers

(ASWB, 2024)

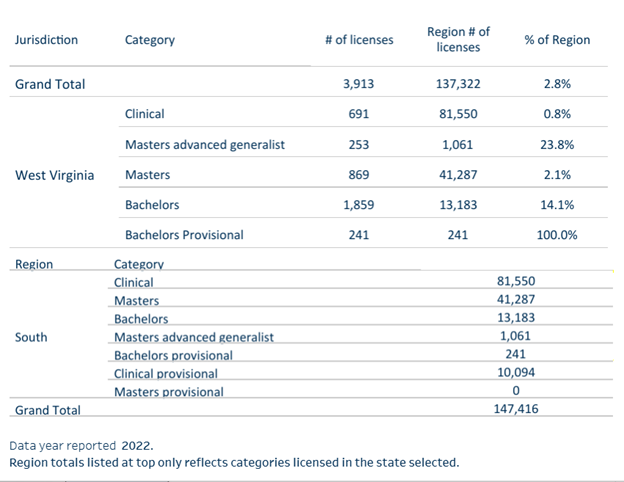

Table 1, Number of Licensed Social Workers in West Virginia, provided by the ASWB (2024) shows that West Virginia has 3,913 licensed social workers. Of these licensed social workers, 241 hold a provisional license. Individuals with a provisional license are not required to obtain a bachelor’s degree in social work, just an unspecified Bachelor of Arts or Bachelor of Science degree. This equates to just over 6% of West Virginia Social Workers practicing without a specialty in social work.

Table 1

Number of Licensed Social Worker in West Virginia

(ASWB, 2024)

Solution

The Department of Defense awarded a $500,000 grant to begin the development of an Interstate Social Work Compact. The Interstate Social Work Compact will work similarly to other professions that have compact agreements, such as counseling and nursing. The goal of the Interstate Social Work Compact is to streamline licensing for social workers. This would eliminate the need to obtain separate licensure in each individual state, provided that social worker intends to practice in a state that has enacted the compact agreement. The compact agreement only requires the professional social worker to apply for license, pay fees, and complete testing in their home state. Despite only applying for licensure in their home states, social workers would be able to provide services in any other state that has joined the compact agreement. This will eliminate licensure portability issues for compact states (National Center for Interstate Compacts, 2024).

The Interstate Social Work Compact will offer many benefits to clients, social workers, states, and administrative boards. For clients, the interstate compact will increase access to treatment. Continuity of care will improve for clients should they need to move. The compact agreement will expand employment opportunities, preserve state sovereignty, reduce administrative burdens, and enhance public safety (National Center for Interstate Compacts, 2024). Further, the licensing compact will standardize scopes of practice and develop consistency in licensing titles (Cooper-Bolinksy, 2019; Morrow, 2023).

To date, fifty percent of the states within the United States have acted on legislation for the Interstate Social Work Compact; however, West Virginia has not. Eighteen states have passed the legislation to enact the agreement: Maine, Vermont, Tennessee, Georgia, Kentucky, Ohio, Virginia, Alabama, Missouri, Iowa, South Dakota, Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, Utah, and Washington. An additional seven states have pending legislation to enact the agreement: Arizona, Louisianna, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire (National Center for Interstate Compacts, 2024).

Given the rurality of West Virginia, enacting legislation to join the compact would enable more social workers to provide services to individuals and families in West Virginia and allow clients more flexibility with choosing a provider. Additionally, access to more providers can reduce the likelihood of dual or multiple relationships occurring. If a dual or multiple relationship arises, increased access to providers in our rural state would make it easier for services to be transferred to another adequately trained provider (National Center for Interstate Compacts, 2024).

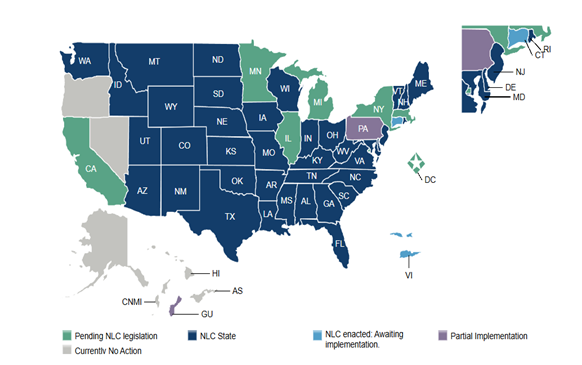

The idea of interstate compacts for professionals is not new. Both nursing and counseling have interstate compact agreements establish. Every state in the United States except for Oregon, Nevada, Alaska, and Hawaii have enacted the interstate nursing compact, See Figure 3 (Interstate Commission of Nurse Licensure Compact, 2024).

Figure 3

Nursing Compact Map

Interstate Commission of Nurse Licensure Compact, 2024

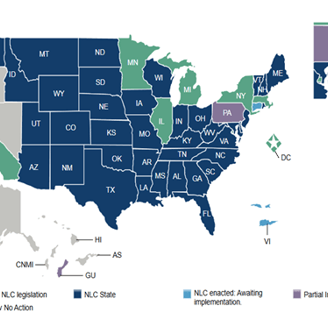

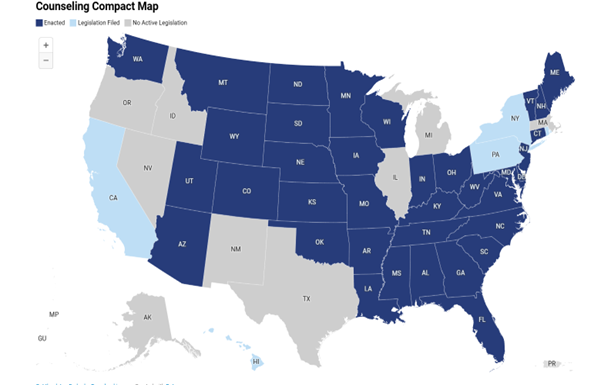

All states in the U.S. except for nine (Oregon, Idaho, Nevada, Alaska, Michigan, New Mexico, Texas, Illinois, and Massachusetts) have enacted the counseling compact or have pending legislation to enact the compact, See Figure 4. In addition to the benefits stated above, the Counseling Compact asserts that interstate licensing agreements streamline investigations of misconduct (Counseling Compact, 2024).

Figure 4

Counseling Compact Map

Counseling Compact, 2024

Limitations to the Interstate Compact Agreement

Limited licensure mobility and portability is a multifaceted issue. It’s, also, not the only issue within the social work licensing framework. Regulatory bodies should consider alternative policies in addition to enacting the Interstate Social Work Compact. These alternative policies should address narrowing the gap between the CSWE and ASWB standards, requiring transparency from the ASWB on examination pass/fail demographics, improving licensure preparation during education, developing inclusive pathways to licensure, and increasing empirical research on licensure outcomes (Cooper-Bolinsky, 2019; Morrow, 2023).

While in support of the Interstate Social Work Compact, Landsman and Rathman (2023) assert that an overreliance on telehealth may be detrimental to individuals in rural communities given the overall risk of suicide in these areas. The authors express concern whether an interstate compact will cause an over reliance on telehealth. However, the study does not assert that providers obtaining licenses in multiple states were relying on telehealth; thus, it would be an assumption that providers within the Interstate Social Work compact would rely solely on telehealth. Additionally, other professions, such as nursing, have enacted interstate compacts without evidence of an overreliance on telehealth (Kim et al, 2023).

Conclusion

In conclusion, current licensure structures create professional barriers for social workers trying to serve rural communities (Dehart et al., 2022; Landsman and Rathman, 2023) and military families. (Apgar and Nienow, 2023; Cooper-Bolinksey, 2019; Kersey, 2023). The licensing framework varies across the United States. The current structure does not provide consistency in licensing titles or scopes of practice. The process for licensure from one state to the next is time consuming, confusing, and expensive. Peer reviewed literature analysis and studies consistently show that poor licensure mobility and portability limits access to safe, adequate, professional mental health treatment creating further risks for individuals and families served (Apgar, 2022; Apgar and Nienow, 2023; Cooper-Bolinskey, 2019; DeHart et al., 2022).

The Interstate Social Work Compact offers a solution to licensure portability struggles. This will benefit areas with critical staffing levels of social workers and prove to be beneficial to rural areas that struggle to access needed services. The interstate compact will standardize the scope of practice and social work titles in the states that join the compact agreement, removing confusing for both providers and clients. While governing bodies need to consider additional policies to advance social work practice, this is the only solution that will streamline licensure in multiple states increasing the access for clients to mental health treatment and case management services.

References

Apgar, D. (2022). Social work licensure portability: A necessity in a post-COVID-19 world. Social Work, 67(4), 381-390.

Apgar, D., & Nienow, M. (2023). Critical time in regulation of social work practice: Forging a path forward. Research on Social Work Practice, 33(1), 3-4.

Association of Social Work Boards. 2024. Laws and Regulations Database. https://www.aswb.org/regulation/laws-and-regulations-database/

Cooper-Bolinskey, D. (2019). An emerging theory to guide clinical social workers seeking change in regulation of clinical social work. Advances in Social Work, 19(1), 239-255.

Council on Social Work Education (CSWE). (2020). Accreditation Standards for Professional Practice Doctoral Programs in Social Work. www.cswe.org/CSWE/media/AccreditationPDFs/ Accreditation-Standards-for-Professional-Practice-Doctoral-Programs-in-Social-Work-June-2020.pdf

Council on Social Work Education (CSWE). (2022). Educational policy and accreditation standards. https://www.cswe.org/getmedia/bb5d8afe-7680-42dc-a332-a6e6103f4998/2022-EPAS.pdf

Counseling Compact. (2024). Counseling Compact. https://counselingcompact.org/

DeHart, D., Iachini, A., King, L. B., LeCleir, E., Reitmeier, M., & Browne, T. (2022). Benefits and Challenges of Telehealth Use during COVID-19: Perspectives of Patients and Providers in the Rural South. Advances in Social Work, 22(3), 953-975.

Interstate Commission of Nurse Licensure Compact. (2024). Nurse Licensure Compact. https://www.nursecompact.com/index.page#map

Kersey, A. W. (2013). Ticket to ride: Standardizing licensure portability for military spouses. Mil. L. Rev., 218, 115.

Kim, J. J., Joo, M. M., & Curran, L. (2023). Social Work Licensure Compact: Rationales, expected effects, and a future research agenda. Clinical Social Work Journal, 51(3), 316-327.

Landsman, M. J., & Rathman, D. (2023). Rural Challenges in Social Work Regulation. Research on social work practice, 33(1), 121-131.

Morrow, D. F. (2023). Social work licensure and regulation in the United States: Current trends and recommendations for the future. Research on Social Work Practice, 33(1), 8-14

Musburger, P., Olson, E., Etow, A., Camilleri, C., Wong, H., Witten, M. H., & Kaminski, J. W. (2024). Examining State Licensing Requirements for Select Master’s-Level Behavioral Health Providers for Children. Psychiatric Services, appi-ps.

National Center for Interstate Compacts. (2024). Social Work Licensure Compact. https://swcompact.org/

Social Work Licensure Requirements by State

Social work licensure requirements vary across the United States. There are not consistent scopes of practice, licensure titles, examination requirements, or requirements for supervision. To highlight some of these issues, we discuss the licensure requirements individually for some states within the United States. To see a full list of licensure requirements, see ASWB reports at Association of Social Work Boards.

Alabama has three licensure levels, Licensed Bachelor Social Worker (LBSW), Licensed Independent Clinical Social Worker (LICSW) and Licensed Master Social Worker (LMSW). The LBSW requires a bachelor’s degree, while the other two require master’s or doctorate degrees. The LMSW and LICSW both require 3,000 hours of supervision. Alaska has the same licensure levels as Alabama. Arizona has a licensed clinical social worker (LCSW) in place of the LICSW and requires 3,200 hours of supervision for the LCSW. Arkansas follows the same structure as Arizona but requires 4,000 hours of supervision for the LCSW. California only has two licensure levels, LCSW and associate clinical social worker (ACSW). The LCSW requires 3000 hours of supervision and the ACSW does not require any, nor requires an exam for the ACSW (ASWB, 2024).

Colorado only has two licensure levels, LCSW and licensed social worker (LSW). Their clinical license requires 3,360 hours of supervision. Connecticut has two levels of licensure, LCSW and a master’s level social worker (MLSW). Connecticut’s MLSW license does not require an exam. Delaware has three licensure levels, LCSW, LMSW, and LBSW. The LCSW in Delaware requires 3,2000 hours of supervision. Florida has three levels of licensure, LCSW, registered clinical social worker intern (RCSW-1), and Certified Master Social Worker (CMSW). The RCSW-1 does not require an exam. The LCSW must pass the clinical exam and the CMSW must pass the advanced generalist exam. Georgia has the LCSW and LMSW, both requiring exams. The LCSW requires 3000 hours of supervision while the LMSW requires two years (ASWB, 2024).

Hawaii has three levels of licensure LCSW, LSW, and LBSW. They follow the same structure as Alabama. The LSW in Hawaii requires a master’s or doctorate degree with a clinical focus. This is different from both Colorado’s LSW and West Virginia’s LSW. West Virginia has five licensure types, LICSW, LCSW, LGSW, LSW, and LSW-P. The LSW-P in West Virginia is a provisional license requiring a bachelor's degree in any behavioral health discipline and four years of supervision. West Virginia’s LICSW license is abbreviated for Licensed Certified Social Worker, instead of Licensed Clinical Social Worker. Idaho has the LCSW, LMSW, and LSW. All of Idaho’s license types require 3000 hours of supervision, but the educational requirements are a Bachelors and master’s in social work like other LCSW, LMSW, and LSW licenses (ASWB, 2024).

Illinois has four license types, LCSW1, LCSW2, LSW1, and LSW2. The LSW 1 and 2 do not require exams but require three years of supervision and a bachelor’s degree. The LCSW1 and 2 require a master’s degree and 3,000 hours of supervision. Indiana has the LCSW, LSW, and LBSW. Their LSW and LCSW both require master’s degrees while their LBSW license only requires a bachelor’s degree. Their LCSW requires two years of supervision, but no set number of hours. Iowa titles their Licensed Independent Social Worker as the LISW, contrary to West Virginia’s LICSW, despite both being a clinical license. Iowa also has the LMSW and LBSW. Kansas titles their clinical license as the Licensed Specialist Clinical Social Worker (LSCSW). Kansas has an LMSW and LBSW with no specific supervision requirements at the levels. The LSCSW requires 3,000 hours of supervision (ASWB, 2024).

Kentucky has four licensure types and throws in some additional social work titles in the mix. While they have the LCSW requiring 3,600 hours of supervision. They have a Certified Social Worker (CSW), Licensed Social Worker 1 (LSW1) and LSW2. The CSW license requires two years of supervision while their LSW1 and LSW2 do not have listed specified supervision. The LSW1 and LSW2 are bachelor’s level social work licenses, while the LCSW and CSW both require at least a master’s degree (ASWB, 2024).

Louisiana has LCSW, MSW, CSW, and registered social worker (RSW). The RSW is the only level of licensure requiring a bachelor’s degree. Louisiana does not require an exam for the CSW or RSW level of licensure. Maine has six types of social work licenses LCSW 1, LCSW2, LMSW-CC (Licensed Masters Social Worker Clinical Conditional), LMSW, LSW1, LSW2-C (LSW-conditional). The LCSW1, LCSW3, LMSW-CC, and LMSW all require a master’s degree. The LCSW1 requires 3,200 hours of supervision while the LCSW2 requires 6400 hours, both require the clinical exam. The LMSW-CC does not require an exam. The LMSW requires the master’s level exam, and the LSW1 requires 3,200 hours supervision, bachelor’s degree, and bachelor’s exam. The LSW2-C has the same requirements as LSW1, except for the exam (ASWB, 2024).

Furthering the complicated social work titles, Massachusetts has eleven (11) types of social work license, each requiring a varying degree of education, supervision, and examination. LICSW, LCSW (Licensed Certified Social Worker), LSW1, LSW2, LSW3, LSW4, LSW5, LSW6, Licensed Social Work Associate 1 (LSWA1), LSWA2, and LSWA3. The LICSW and LCSW both require clinical exams and master’s degree. The LSW1 and LSW2 both require a bachelor’s degree. However, the LSW3 requires 2.5 years of college and 8750 hours of supervision upon licensure. The LSW4 requires two years of college and 10500 hours of supervision. The LSW5 requires one year of college and 14000 hours of supervision. The LSW6 requires a high school diploma and 17.500 hours of supervision. All LSW1 through LSW6 require the bachelor’s level examination. The LSWA1 requires a Bachelor of Arts or Science degree, but it does not have to be specific to social work. This level requires the Associates level exam. The LSWA2 requires a two-year college degree and the associate level exam. The LSWA3 requires a high school diploma, associate level exam, and four years of supervision (ASWB, 2024).